As the UK government pushes forward with plans for a new generation of towns, experts and urban planners are turning to an unlikely but insightful source of inspiration: medieval France. The bastides—a network of meticulously planned towns built across south-western France in the 13th and 14th centuries—offer valuable lessons for shaping vibrant, walkable, and economically sustainable communities today.

Ancient Urban Planning with Modern Relevance

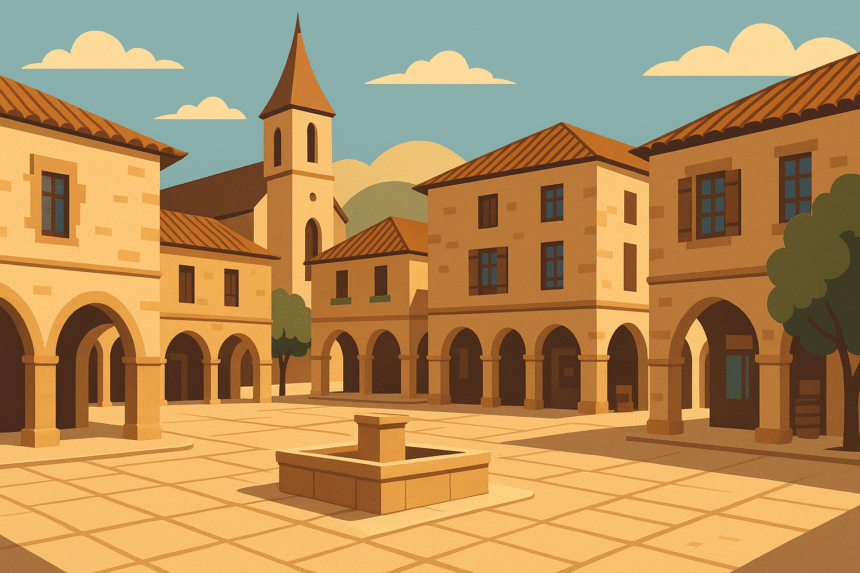

Unlike most medieval European towns, which grew haphazardly, bastides such as Monpazier, Villeréal, and Sauveterre-de-Guyenne were built on grid systems with central squares, arcades, and designated commercial hubs. These towns were designed for commerce and community, with markets held regularly for centuries—some dating back to the 1200s.

Today, many of these towns remain thriving and walkable. Their compact design, mixed-use central squares, and resident-centric amenities such as local shops, pharmacies, cafés, and butchers make them attractive places to live. In an era when small towns often suffer from depopulation and disappearing services, bastides have preserved both their charm and their function.

Lessons for Modern New Towns

The UK’s New Towns Taskforce, chaired by Sir Michael Lyons, has been charged with recommending new town development strategies that aim to deliver hundreds of thousands of homes by 2050. Lyons notes that many proposals are extensions of existing cities, though some stand-alone settlements are being considered.

While much attention has been placed on learning from postwar British new towns, experts suggest looking further back. Bastides demonstrate the power of master planning, where walkability, commercial vibrancy, and community cohesion were baked into the design from the beginning.

This is echoed by Nigel Hugill of the Centre for Cities and Julia Thrift of the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), who stress the importance of designing towns that foster casual social interaction, active lifestyles, and resident engagement—the very principles at the heart of the modern “15-minute city” concept.

Compact, Walkable, and Social by Design

Bastides were originally home to just 500 to 1,000 residents—far smaller than today’s urban needs—but their core principles remain relevant. Their density, while modest, supports local shops and services, avoiding the isolating sprawl of many contemporary developments. As Lyons puts it, “quiet densification” is key—it doesn’t mean building tower blocks, but ensuring town centres are lively and accessible.

Equally important are flexible spaces. In bastides, the covered arcades and market squares now house modern businesses from florists to estate agents—proof that adaptable infrastructure can endure across centuries. New towns should avoid sterile, monolithic shopping centres and instead build multi-use spaces that evolve with community needs.

Governance, Investment, and Stewardship

The success of past new towns in the UK—like Milton Keynes—was partly due to development corporations that were empowered to plan, invest in infrastructure, and reinvest returns. Lyons argues that modern equivalents are essential, offering long-term stewardship, land acquisition capabilities, and coherent planning authority. Without such models, as seen in the asset fire sales of the 1980s, public benefit can quickly erode.

Experts also point out that property developers alone cannot deliver the kind of civic infrastructure necessary for thriving towns. As Hugh Ellis of the TCPA notes, even mining companies in the 1920s built better worker housing than what some modern developers offer. New towns must go beyond housing and ensure there are jobs, schools, healthcare, and community spaces.

Identity, Liberty, and Local Ownership

The bastides succeeded not only because of their physical design, but also because they offered early charters of liberties—contractual rights that gave residents autonomy and protection. Today, community engagement and even local ownership models are seen as critical to long-term success. Some modern town projects have already begun transferring community halls and assets into local hands, creating more responsive and resilient places.

A Blueprint for Modern Living

Ultimately, England’s new towns must be more than housing estates—they must be places of belonging. The bastides succeeded because they were built with civic intentionality: to support commerce, community, and quality of life. Modern towns can emulate this by ensuring mixed-use spaces, compact design, and robust governance that ensures ongoing care and adaptation.

As one resident of Villefranche-du-Périgord noted while sipping coffee under the arcades of Monpazier: “They’re unspoilt, untouched.” That enduring vibrancy is not an accident—it’s the result of thoughtful planning, heritage protection, and community care. If England’s new towns can adopt even part of this model, they too could be thriving 800 years from now.