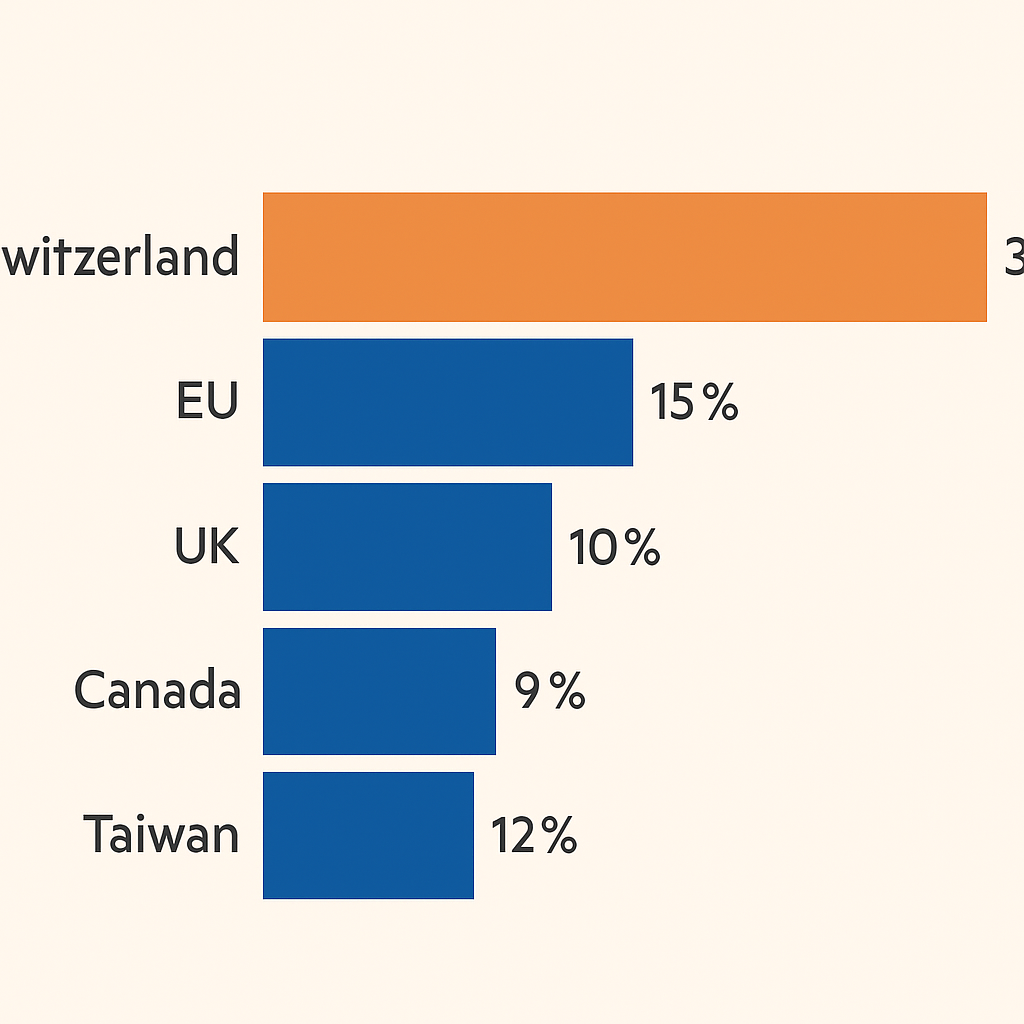

Switzerland, rarely at the centre of global trade disputes, now finds itself facing one of the harshest tariff measures imposed by the United States under President Donald Trump’s trade agenda. Earlier this month, Washington imposed a 39% tariff on most Swiss goods, more than double the average rate applied to the EU and higher than those levied on the UK, Canada, or any other developed country.

The punitive action followed the expiration of a seven-day grace period, leaving Swiss officials scrambling for a response. While Bern has pledged to continue talks with Washington, the scale and targeting of the measure have shocked policymakers and industry alike.

A Disproportionate Hit

The US justified the move by citing Switzerland’s CHF 48.5bn ($60bn) goods surplus with the US in 2024, paired with limited imports from America. The new tariff covers almost all product groups, with only narrow exemptions — notably gold and pharmaceuticals — bringing the effective average rate down to just over 12%.

Still, major export sectors such as watches, machinery, industrial tools, and chocolate were hit immediately. Even exemptions have proven uncertain: US tariffs were applied to 1kg gold bars last week, hurting Switzerland’s position as the world’s largest gold refining hub.

The disparity in treatment has raised eyebrows. The EU negotiated an average rate of 15%, the UK secured 10%, and Taiwan capped tariffs at 20% with phased exemptions. Switzerland, by contrast, appears isolated.

Structural Weakness in Negotiations

Analysts and Swiss politicians suggest the issue lies not in Swiss actions but in its institutional constraints. Switzerland’s consensus-driven government, direct democracy system, and tradition of neutrality limit its ability to make large, politically bold offers in negotiations.

Unlike the EU or Japan, Switzerland lacks the market size or geopolitical leverage to threaten retaliation in defence, energy, or other strategic areas. It also cannot promise large-scale investment packages akin to the EU’s $750bn US energy pledge.

As Hans-Peter Portmann, Swiss banking executive and politician, noted: “Switzerland has a reputation for delivering on its commitments. But that can be a weakness in a world that rewards drama and ambition… that’s a problem when you’re up against Trump.”

Limited Levers and Risky Options

Potential Swiss responses are politically sensitive and technically difficult. Ideas under discussion include:

- Targeted US investments in exchange for tariff relief – though the government cannot commit private sector capital.

- Increased LNG purchases – largely symbolic, as Switzerland lacks import infrastructure and consumes little gas.

- Defence procurement leverage – modifying or cancelling its $9bn order for US F-35 fighter jets.

- Agricultural market access – politically risky and likely to trigger a referendum.

- Gold trade policy – preferential tariffs or new levies on foreign refiners, though complex and potentially disruptive.

- Soft-power diplomacy – using FIFA President Gianni Infantino, a Swiss national with ties to Trump, as an intermediary.

Private Swiss multinationals like Roche and Partners Group are also lobbying in Washington to seek a resolution.

A Test of Swiss Economic Sovereignty

The dispute has triggered a wider debate within Switzerland about whether its go-it-alone model remains viable in an era of aggressive bilateralism. With no customs union, no US free trade agreement, and no bloc-level backing, Switzerland has faced the tariff confrontation alone.

Some officials and industry groups are now questioning whether closer alignment with the EU could offer greater protection in the future.

For now, Switzerland must decide whether to make politically sensitive concessions, seek a symbolic compromise, adapt to the tariffs, or wait out Trump’s administration. But the broader question remains: in today’s geopolitical economy, has Switzerland’s long-cherished neutrality and regulatory independence become a strategic liability?