The debate over the four-day work week often divides opinion. Supporters argue it can ease burnout, promote gender equality, reduce unemployment, and even lower carbon emissions. Critics warn it could harm productivity, weaken competitiveness, strain public services, and erode work ethic.

Yet rather than relying on predictions or small-scale trials, the Netherlands offers a living example of how reduced working hours can function within a modern economy.

A Nation of Shorter Hours

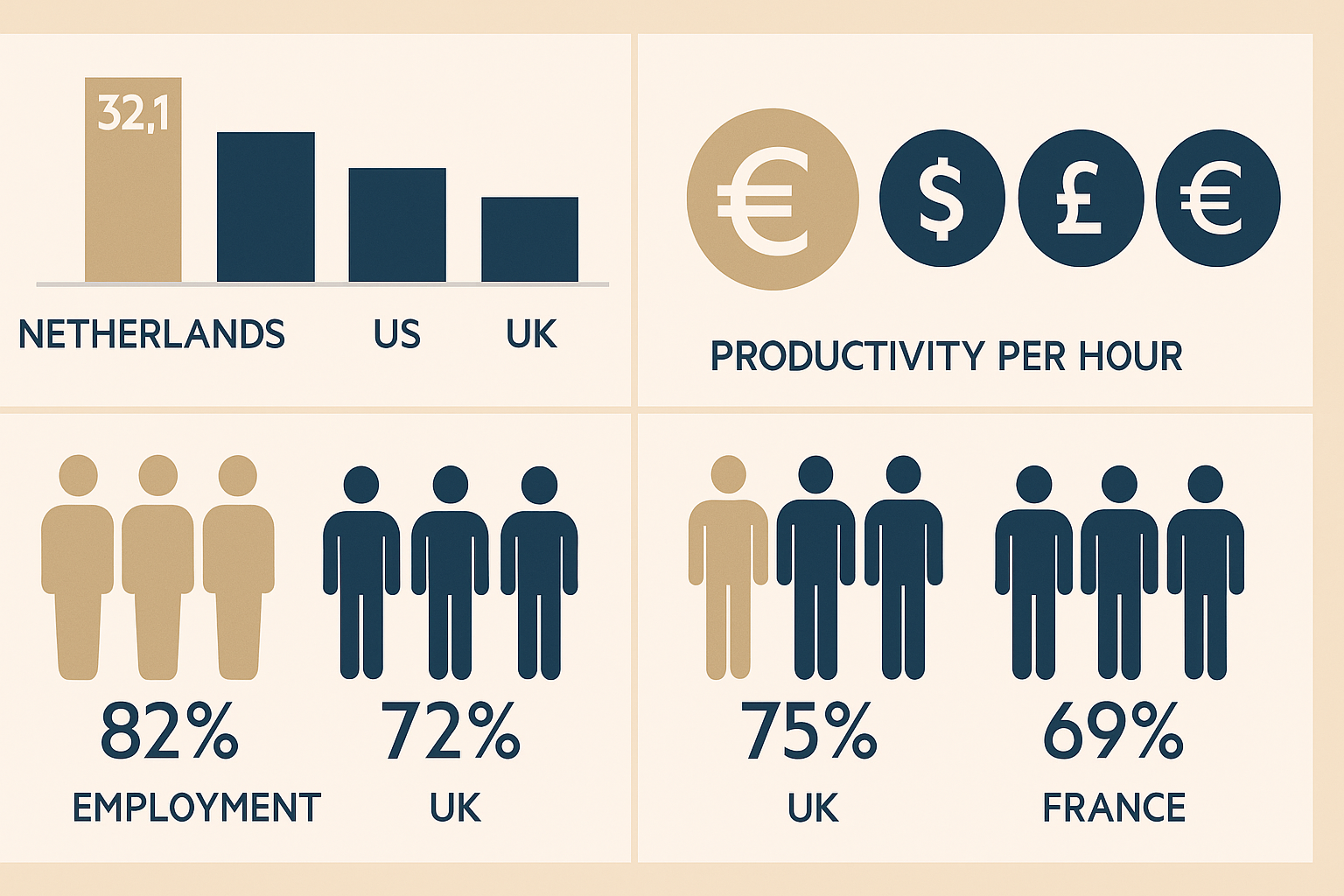

According to Eurostat, the average working week for people aged 20 to 64 in the Netherlands is just 32.1 hours — the shortest in the European Union. Many Dutch employees compress these hours into four days rather than five, a practice that has become widespread. “The four-day work week has become very, very common,” notes Bert Colijn, an economist at ING.

The trend stems from the 1980s and 1990s, when women entered the workforce in large numbers through part-time roles. Over time, this created what has been described as a “one-and-a-half earner model,” reinforced by tax and welfare policies. As part-time work became more socially accepted, increasing numbers of men, particularly fathers, also began reducing hours to spend more time with family.

Economic Implications

Despite shorter working hours, the Netherlands remains one of the wealthiest EU economies per capita. The key lies in high productivity per hour and broad workforce participation. At the end of 2024, 82 per cent of working-age people in the Netherlands were employed, compared with 75 per cent in the UK, 72 per cent in the US, and 69 per cent in France.

Women’s employment rates are particularly high compared with longer-hour economies such as the US. Moreover, Dutch workers often retire later, spreading their labour contributions across a longer span of life.

Gender and Social Trade-Offs

However, shorter working hours have not resolved gender inequality. Women are still far more likely to work part-time than men, and this often slows career progression. In 2019, the OECD reported that only 27 per cent of managers in the Netherlands were women, one of the lowest shares among developed economies.

Labour shortages are another challenge, particularly in education and healthcare. Shortages can create instability in services like schooling, which in turn makes it harder for parents to commit to longer working weeks.

Beyond Economics

Economist Colijn acknowledges that the Netherlands may be “holding itself back” by limiting working hours. Yet he warns against pursuing growth at the cost of quality of life: “I wouldn’t want to propose any dystopian society where everyone is working more than Korean hours, just because it increases GDP.”

The Dutch model suggests that a shorter work week is not a perfect solution, but neither is it a path to economic collapse. Instead, it shows that societies can organize and distribute work differently, with trade-offs between economic output, social well-being, and family life.

One additional benefit often overlooked: Dutch children consistently rank among the happiest in the developed world, a reflection of the balance between work, family, and leisure in Dutch society.