Romania’s government has introduced a series of austerity measures aimed at reining in its record budget deficit, reviving memories of unpopular cuts and tax hikes that toppled governments across Europe more than a decade ago.

Finance Minister Alexandru Nazare confirmed that the first package of measures — which came into effect on August 1 — includes raising the top VAT rate from 19% to 21%, increasing excise duties, and freezing public sector wage and pension increases until 2026. Two further austerity packages are planned for later this year, despite protests partly driven by the far-right AUR party.

Romania’s public deficit reached 9.3% of GDP in 2024, the highest in the EU and well above the bloc’s 3% limit. The previous government avoided austerity ahead of last year’s elections, leaving the new coalition to confront the problem.

Public opposition is intense. In 2012, Romania implemented one of Europe’s harshest austerity programs after the sovereign debt crisis, leading to mass protests and the collapse of the government. This year, hundreds have taken to the streets again, with AUR leader George Simion calling for early elections and urging citizens to refuse paying what he calls illegitimate taxes.

The government says deeper reforms are still ahead. These include overhauling state-owned company governance and cutting “special privileges” in the pension system, such as early retirement for judges. Nazare said these steps are “essential to ensuring both fiscal sustainability and fairness.”

The austerity program comes as Romania faces a challenging economic outlook. Growth slowed to 0.3% in the second quarter, inflation remains high, and interest rates are stuck at 6.5%. Ratings agencies have downgraded Romania to just one notch above “junk” status.

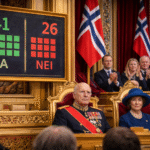

The political backdrop is fragile. The current four-party coalition, led by pro-EU President Nicușor Dan, came to power in June after a rerun presidential election annulled the previous year over alleged Russian interference. Internal tensions persist, with recent resignations and disputes over state ceremonies fueling instability.

Meanwhile, AUR — which placed second in December’s parliamentary elections — has surged to about 40% in opinion polls, capitalizing on public dissatisfaction over the cost of living and perceptions of political corruption.

Some of the most controversial pending measures, particularly pension reform and changes to state company governance, are tied to accessing the EU’s post-pandemic recovery funds. Romania risks losing nearly a quarter of its original €28.5bn allocation, having drawn less than €10bn so far.

Nazare insists the coalition is committed to maintaining access to these funds, accelerating public sector digitalization, improving tax collection, and targeting regulators in sectors like energy and telecommunications to cut costs and boost transparency. However, he acknowledged that many reforms will likely be completed only toward the end of the government’s three-year term.

Political analysts are skeptical about the coalition’s longevity. Costin Ciobanu of Aarhus University said the fear of losing to AUR might keep the alliance together in the short term, but “I’m not very confident that the coalition can last more than a year.”

Public trust remains low. “Everything has become more expensive with the increase in VAT,” said Cristina, a 49-year-old engineer in Bucharest. Mihai, a 53-year-old worker, added: “If I and others paid our taxes, where did the hole come from? Someone did something wrong — let that someone pay.”