The Bayeux Tapestry, an 11th-century embroidery depicting the Norman conquest of England in 1066, has long been more than just an artefact. Across centuries, it has served as a political and cultural instrument — Napoleon considered it a propaganda tool to bolster his plans to invade Britain, the Nazis were drawn to its symbolism, and now, over 900 years after it left English soil, it is set to return to the UK as a gesture of post-Brexit rapprochement with France.

When it arrives at the British Museum in 2026, the 70-metre-long piece will headline what museum chair George Osborne has called “the blockbuster show of our generation.” Its vivid, comic strip-like scenes — ambition, betrayal, war, and death — are not only a national historical treasure but also a global cultural icon. Created in England by nuns, the work contains 623 men, 190 horses, 37 ships, 35 dogs, and just three women, making it both a detailed record and a subject of enduring fascination.

Diplomacy Behind the Loan

The return is the result of years of behind-the-scenes diplomacy. French President Emmanuel Macron first floated the idea in 2018 during a meeting with then-Prime Minister Theresa May, but the plan stalled due to political resistance in France, lack of momentum, and pandemic disruptions. Talks revived this year, as London and Paris sought to use a depiction of English defeat as a symbol of renewed friendship. The agreement became a centrepiece of the UK-France summit in July, endorsed by Macron and King Charles III.

The cultural exchange will see Britain lend treasures to France, including the Sutton Hoo artefacts and the Lewis Chessmen. Negotiations were conducted in strict secrecy, even excluding potential rival hosts such as the Victoria and Albert Museum. Disputes over transport costs and suggested special admission for French visitors were resolved, with both sides agreeing instead to prioritise access for children.

Challenges of Moving a National Treasure

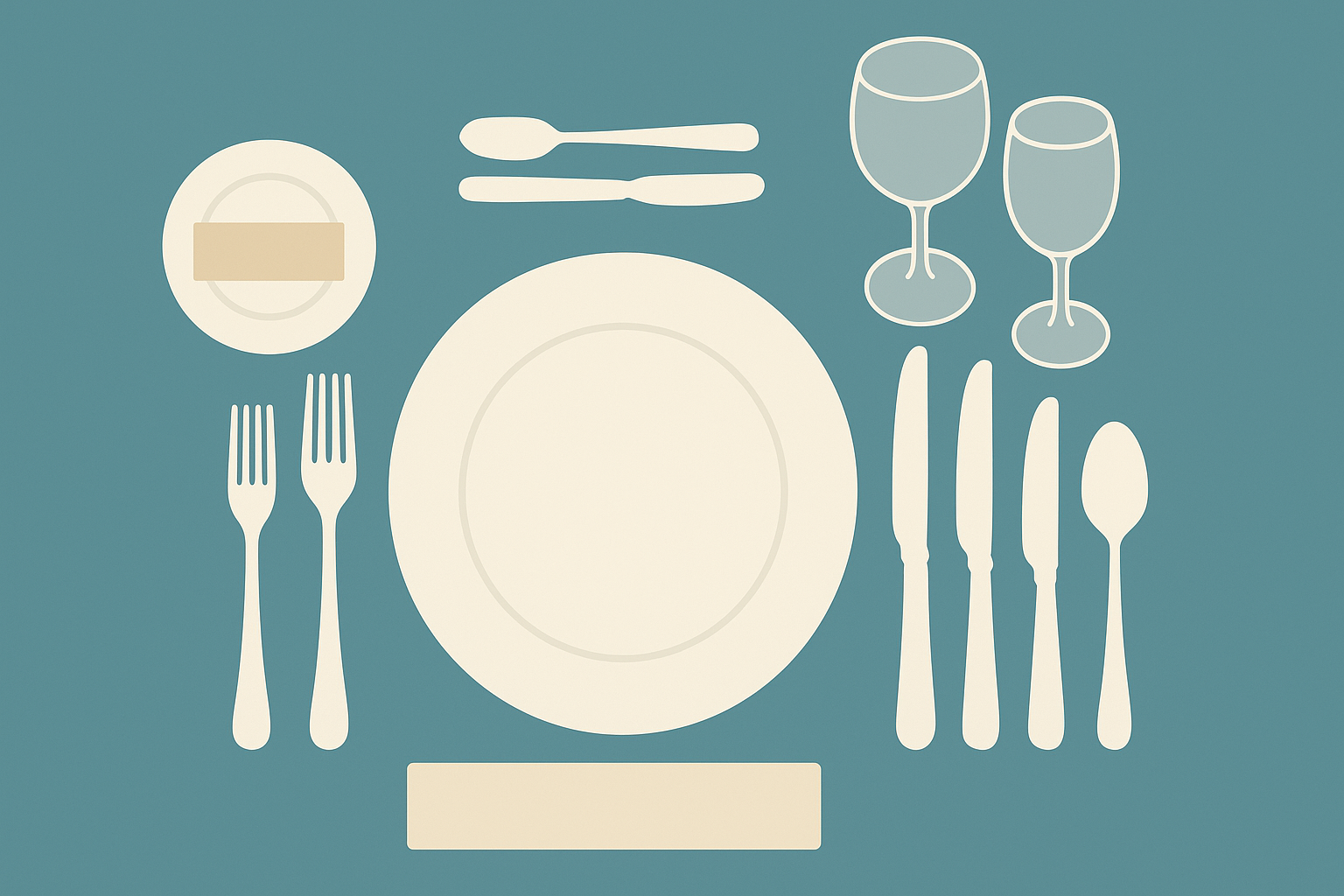

Transporting the tapestry is a logistical challenge, with costs expected in the millions and extensive insurance guarantees required. Textile experts in Bayeux have devised a meticulous plan to move it safely, using a custom metal screen system to prevent stress and damage. Once in London, it will be displayed flat on inclined tables to reduce strain — a departure from its traditional hanging.

History of Loan Attempts

Previous British requests to display the tapestry — in 1953 for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation and in 1966 for the Battle of Hastings’ 900th anniversary — failed due to political and technical hurdles. This loan is possible now only because its home museum in Bayeux is undergoing a €38 million renovation. The work will be housed in a new, modern wing in France after its return, displayed in a straight line for the first time.

French Hesitation and Presidential Will

The proposal has been divisive in France. Cultural officials and textile conservators voiced concerns, citing the artefact’s fragility — a 2020 inspection found tens of thousands of stains, gaps, and tears. However, Macron, like Charles de Gaulle before him with the loan of the Mona Lisa to the US in 1963, chose to override expert objections, viewing cultural diplomacy as vital to Franco-British ties.

A Symbol of Shared History

For many in Britain, the tapestry has always held a special place — perhaps even more so than in France. Its loan, coinciding with broader defence and migration cooperation, is meant to demonstrate that the relationship between the two nations can transcend Brexit-era tensions. As UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer put it at the announcement: “Everybody is walking around here with a smile on their face.”